LGBTQ+ Art: From Classical to Contemporary

LGBTQ+ art is not a recent phenomenon nor solely a part of contemporary art. In contemporary art, it has been "codified" or better yet "institutionalized."

|

| Keith Haring - Ignorance = Fear Silence = Death |

In fact, two major classical artists, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, were

gay and created art that reflected their appreciation of the male form.

Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel, with its detailed depictions of the male body,

and Leonardo's deep study of the Vitruvian Man are prime examples.

Throughout history,

other gay artists have also made significant contributions. For instance, RosaBonheur, a French painter known for her animal paintings, and Grant Wood, an

American artist famous for "American Gothic," both challenged gender

norms and expressed queer themes in their work .

Contemporary Art: From Pain and Protest to Presence and Power

In the early 1980s, a

quiet revolution was unfolding in studios, underground clubs, bedrooms, and

activist spaces. LGBTQ+ artists, often ignored, misrepresented, or excluded

from mainstream galleries, were reshaping the world of contemporary art. Amid

the looming specter of the AIDS crisis, a new visual language began to emerge:

one forged through pain, but also through love, eroticism, identity, and

radical resilience.

|

| Patrick Angus - Material World |

This is the story of

how queer art, from the margins, redefined the center. And within this story

stands Patrick Angus, a forgotten yet essential voice whose paintings gave

visibility to a world few dared to depict.

Beauty Amidst the Shadows – PatrickAngus and the Era of Loss

The 1980s were marked

by silence and devastation. The AIDS epidemic hit the LGBTQ+ community with

unprecedented cruelty, exacerbated by government inaction and widespread

societal stigma. Art became a site of both mourning and militant resistance.

Patrick Angus (1953–1992), often described as the “lost painter of the AIDS generation,”

captured an aspect of queer life that few dared to portray. His paintings,

filled with tender eroticism and aching melancholy, chronicled the lives of gay

men in New York’s Times Square peep shows and strip clubs, not as caricatures

or fantasies, but as real, vulnerable human beings.

Works like "Hanky

Panky," "The Apollo Room," and "Grand Finale," with

their vivid colors and voyeuristic yet empathetic gaze, speak volumes about

loneliness, desire, and the search for connection in a world that reduced queer

bodies to taboo. Angus portrayed the performers not as anonymous objects but as

people longing to be seen.

His work was raw,

intimate, and utterly human, yet he received little institutional recognition

during his lifetime. He died at 38, from AIDS-related complications, leaving

behind a body of work that has only recently begun to receive the attention it

deserves. In many ways, Angus stood as a bridge between the invisibility of the

past and the visibility queer artists would later claim.

Felix, David, Keith: The Art of Resistance

While Patrick Angus

painted his quiet tragedies, other queer artists responded to the AIDS crisis

with bold confrontation, each using their unique artistic voices to challenge

societal indifference and stigma.

David Wojnarowicz used rage as his medium, creating powerful works that combined photography, text, and iconography to expose the hypocrisy of a system that allowed people to die in silence. His piece "Untitled (One Day This Kid…)" is a poignant example.

.jpg) |

| David Wojnarowicz - Untitled (One Day This Kid…) |

Felix Gonzalez-Torres countered the brutality of the AIDS crisis with subtlety and poignancy. His work "Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)" consists of a pile of candies, each individually wrapped, representing the ideal body weight of his partner, Ross Laycock, who died of AIDS-related complications. Visitors are invited to take a piece of candy, symbolizing the gradual loss of Ross's body weight and, by extension, his life.

%20main.jpg) |

| Felix Gonzalez-Torres - Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) |

Keith Haring brought queer culture into public spaces with

his bold lines and visually accessible style. His murals and street art,

characterized by radiant babies, barking dogs, and dancing figures, became

symbols of both joy and urgency. Haring's work was not just art; it was

activism. He used his visibility to fight stigma and raise awareness about

AIDS, creating pieces like "Silence = Death," which directly

addressed the epidemic and its impact on the LGBTQ+ community. Haring's art was

a call to action, urging society to confront the crisis head-on.

|

| Keith Haring - Silence = Death |

These artists, through

their diverse approaches, transformed their pain and anger into powerful

statements of resistance and resilience. Their work continues to inspire and

challenge, reminding us of the ongoing struggle for visibility and justice.

Queer Theory, Queer Bodies

The 1990s saw LGBTQ+

artists pushing further into the realm of identity, performance, and

intersectionality. Influenced by the rise of queer theory and a growing

awareness of race, class, and gender dynamics, artists like Catherine Opie, NanGoldin, and Zackary Drucker began to document the queer body with new intimacy

and defiance.

|

| Nan Goldin - Gotscho kissing Gilles |

Opie’s self-portraits,

such as "Self-Portrait/Pervert," made the body both political and

poetic. Nan Goldin, meanwhile, chronicled queer subcultures through personal

storytelling, capturing moments of tenderness, addiction, violence, and survival.

The performance scene

also exploded, with queer artists embracing drag, transformation, and bodily

modification as forms of resistance. Art wasn’t just made, it was lived.

Transnational, Transgender, and Technological

In the 2000s, queer art

burst beyond Western borders. Zanele Muholi, a South African visual activist,

documented Black queer life with fierce pride. Akram Zaatari, Wu Tsang, and

Juliana Huxtable challenged binaries, using new media to blur the line between

performance and identity.

|

| Juliana Huxtable |

In this era, queer art

became global, intersectional, and digital. The Internet gave LGBTQ+ artists

new ways to share, survive, and build community, even when physical spaces

remained unsafe.

The Post-Binary Turn and Queer Futures

Today, queer art is

many things: political and sensual, angry and ecstatic, deeply local and

cosmically expansive. Artists like Cassils confront violence and transformation

through endurance performance, while others explore queer ecology,

Afrofuturism, and speculative realities.

We now see mainstream

museums showcasing once-marginalized LGBTQ+ art, but many questions remain: Who

is included in the canon? Whose queerness is still invisible?

And in that reflection,

Patrick Angus re-emerges, not as a footnote, but as a precursor. His gaze was

never sensational. He painted loneliness and desire not for applause, but

because no one else was doing it. In Angus's men, we find early echoes of today's

conversations about agency, stigma, and beauty. His legacy is not just

artistic, it’s human.

The AIDS Memorial Quilt

The AIDS Memorial Quilt: A Historical and Artistic Legacy

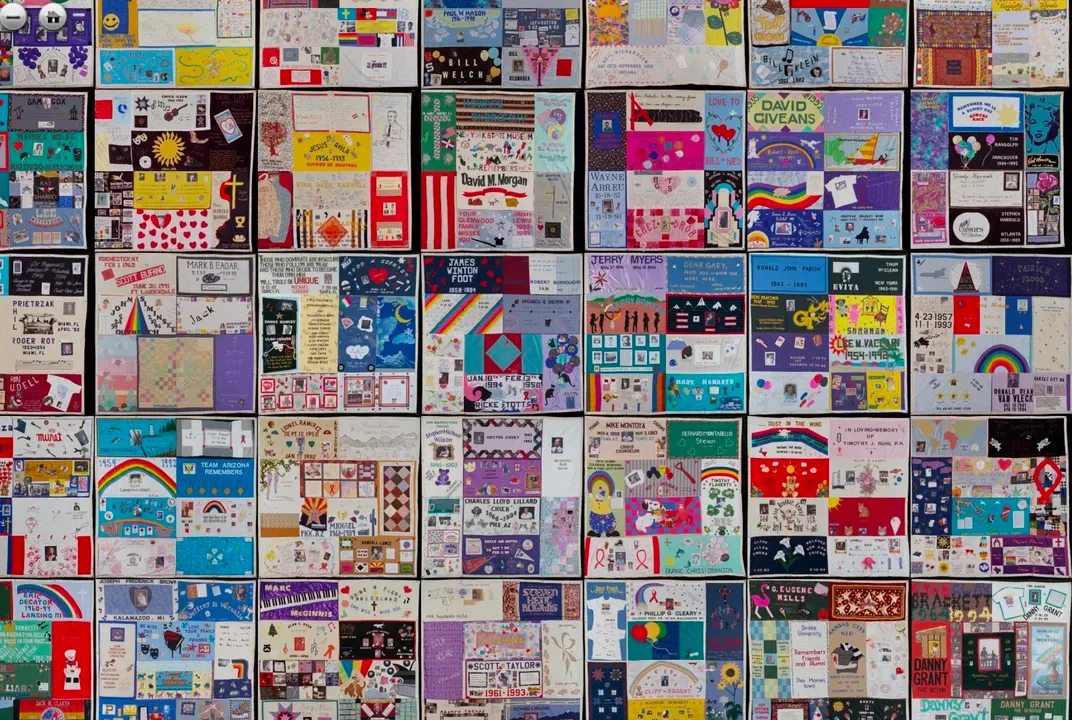

One of the most

poignant symbols of the AIDS crisis is the AIDS Memorial Quilt, conceived in

1985 by activist Cleve Jones. This massive tapestry, weighing 54 tons and

consisting of roughly 50,000 panels, commemorates over 110,000 individuals lost

to HIV/AIDS.

|

| The AIDS Memorial Quilt 2 |

Historical Beginnings

The idea for the Quilt

was born during the annual candlelight march in remembrance of the 1978

assassinations of San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor GeorgeMoscone. During the 1985 march, Cleve Jones asked participants to write the

names of friends and loved ones who had died of AIDS on placards. These

placards were then taped to the walls of the San Francisco Federal Building,

creating a visual patchwork that resembled a quilt.

Inspired by this sight,

Jones and a group of friends decided to create a larger memorial. In June 1987,

they formally organized the NAMES Project Foundation and began collecting

panels from across the United States. The Quilt was first displayed on October

11, 1987, on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., during the National March

on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. It covered a space larger than a

football field and included 1,920 panels. The reading of names, a tradition

that began at this inaugural display, continues at nearly every Quilt

exhibition.

|

| The AIDS Memorial Quilt |

Artistic Significance

The AIDS Memorial Quilt

is not just a memorial; it is a powerful piece of community folk art. Each

panel measures three by six feet, approximately the size of a grave,

symbolizing the connection between AIDS and death. Panels are created by

friends, family members, or loved ones of those who have died, using fabric and

various materials to personalize each tribute. This makes the Quilt a deeply

intimate and personal artwork, reflecting the lives and stories of those commemorated.

|

| The AIDS Memorial Quilt - Detail |

Cultural Impact

The Quilt has been

displayed in various locations, including the National Mall in Washington,

D.C., several times. It returned to San Francisco in 2020, where it is cared

for by the National AIDS Memorial. The Quilt can also be viewed virtually,

allowing people worldwide to connect with its powerful message.

|

| The AIDS Memorial Quilt - detail |

The AIDS Memorial Quilt

serves as a living memorial to a generation lost to AIDS and as an important

HIV prevention education tool. It has been viewed by millions and has raised

significant funds for AIDS service organizations. The Quilt's impact extends

beyond its physical presence, fostering awareness, empathy, and action in the

fight against HIV/AIDS.

My Hopes for the Future

Hopefully, one day the

AIDS Memorial Quilt will be exhibited in a gallery, as it is a vital part of

history and art. Its sheer size and emotional weight require a large space, but

its inclusion in mainstream art institutions would further validate the experiences

and memories it represents.

The Ongoing Revolution

LGBTQ+ art since the

1980s has been about visibility, yes, but more than that, it has been about

truth. It has carved space for grief, sex, rage, tenderness, transformation,

and reinvention. It has refused to die in silence, and it continues to speak

where society still falters.

From the quiet intimacy

of Patrick Angus to the confrontational performances of Cassils, queer art

remains one of the most dynamic and necessary forces in the cultural landscape.

It reminds us that to

be queer is not just to exist differently, it is to see differently, create

differently, and to challenge the world to do the same.

%20at%20Pen%20and%20Brush..png)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment