How Rauschenberg’s groundbreaking “Combines” blurred the line between painting, sculpture, and life itself

Robert Rauschenberg was a visionary who helped define Neo-Dada, bridging the gap between Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art. His groundbreaking Combines—hybrid works built from paint, collage, and found objects—refused tidy categories. Neither purely painting nor sculpture, they collapsed the distance between art and everyday life. This post explores Rauschenberg’s formation, the birth of the Combines, and their lasting influence on contemporary art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born Milton Ernest Rauschenberg in 1925 in Port Arthur, Texas, he initially studied pharmacology before serving in the Navy during World War II. After the war, he trained at the Kansas City Art Institute, the Académie Julian in Paris, and Black Mountain College in North Carolina, encountering pivotal mentors such as Josef Albers and John Cage. Early works reflected Abstract Expressionism, but he soon shifted toward a practice more entangled with the physical world—objects, images, and chance.

The Birth of the Combines

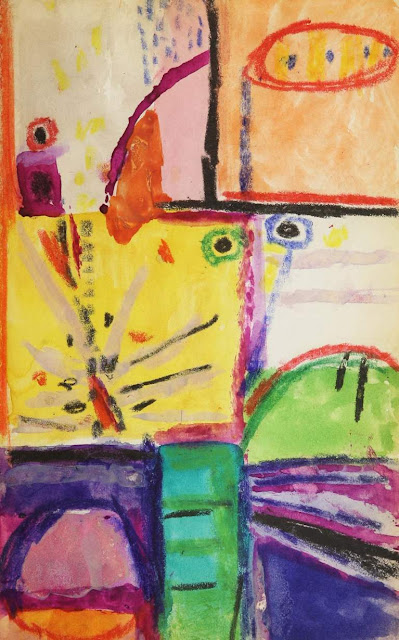

In the mid-1950s, Rauschenberg began the works he called Combines: three-dimensional canvases encrusted with found materials, collapsing distinctions between painting and sculpture. Scavenging New York’s streets, he embedded newspapers, photographs, textiles, furniture fragments, taxidermy, and automobile parts into painterly surfaces.

Among the most iconic is Monogram (1955–59): a taxidermy goat encircled by a tire, poised atop a collage-laden base. The uncanny juxtaposition of animal, object, and image turns everyday debris into a charged theater of meaning.

The Integration of Art and Life

Rauschenberg rejected art as isolated and sacred. In Bed (1955), a quilt and pillow hang vertically like a canvas, slashed and spattered with paint—colliding the intimacy of a bedroom with the gestural bravura of Abstract Expressionism. Canyon (1959) incorporates a stuffed bald eagle within a collage of photos and fabric: national symbol meets urban detritus, patriotism meets parody.

The Influence of Dada and Surrealism

The Combines extend Dada’s challenge to artistic convention—echoing the legacy of Marcel Duchamp’s readymade—while tapping Surrealism’s dreamlike disjunctions. Works like Odalisk (1955–58) stack painterly, sculptural, and collaged elements into a totem of humor, desire, and estrangement.

Legacy and Impact

Rauschenberg paved the way for Pop Art, Assemblage, and Installation. He influenced peers and successors—from Jasper Johns to Andy Warhol, and later artists who deploy found objects and provocative juxtapositions. By erasing borders between media and between art and life, the Combines expanded what art could be—more inclusive, open, and democratic.

Reflecting on Rauschenberg’s Artistic Journey

Rauschenberg’s art invites us to trace connections among the ordinary and the extraordinary. Through layered materials and nimble humor, he urges us to find meaning in the overlooked and to accept messiness as a creative force.

Conclusion

Rauschenberg’s Combines remain a landmark in postwar art—hybrid, restless, and alive to the present. By welding nontraditional materials into hybrid forms, he redrew the parameters of artistic practice and offered a template for generations to come.

%20at%20Pen%20and%20Brush..png)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment